In A Mathematician’s Lament, Paul Lockhart roundly decries the way our school system sucks the soul out of mathematics; what was forced down most of our throats was an insipid husk of repetitive calculation, plug-in formulae, and rigid formality, all of which we were called upon biweekly to regurgitate. Most painful for him to see is the way geometry is taught:

If you haven’t read the Lament yet, definitely stop what you’re doing and take the next 30 minutes to do so; if you have any interest at all in mathematics or education, it will be one of the best-spent half-hours of your life.

Having deep, abiding interests in both of these things, I was personally moved by the piece and feel a renewed enthusiasm for shapes and numbers, an enthusiasm that was all but aborted by my own early math education. Yours almost certainly was too! Here’s what I mean…

Consider a line segment 2 units long. Now, make a square where each side is one of these segments. We have “squared” our 1D segment and we got a 2D shape 2 units long by 2 units wide. That’s 4 square units total, because $22=2x2=4$. Thus, we say that the area of our square is 4 square units! (Area is just an arbitrary measure of what you get when you compare the shape to squares of a fixed size, in this case 1 square unit.)

We can take these 4 square units and arrange them however we want: if we put them all four in a row, we create a rectangle 4 units wide by 1 unit tall. It has the same area as the square; we can see this by inspection or by noticing that $2\times 2=1\times 4$. It is true for all rectangles and parallelograms that area = length x width.

Instead of memorizing a formula, how could we find the area of a triangle?

Is there a way we can cut the square to make triangles? Yes, absolutely. Cut a square diagonally and you get two triangles. Are these the same size? Yes! So if two equal parts make 1, we know they have to be half of the original. Thus, the formula you had to memorize in grade school makes some obvious, visually verifiable sense. You were told, “base times height divided by 2” or “one half base times height”. Well, now you see that “base times height” gives you the area of a rectangle, and “divided by 2” gives you exactly half of the rectangle’s area, corresponding to a triangle.

Teaser: how much of the box is taken up by each of the triangles below?

Here’s a hint:

Answer:

!It’s always half!

The Diagonal of a Square

Now then, let’s take just one of our square units (from earlier). Here’s a question: measure from corner to corner diagonally, and what do you get?

Well, we can see that it’s longer than 1, but shorter than 2. Indeed, 1.5 is a pretty good guess, but it look to be a bit less. 1.4? A bit more than this. 1.41?

Let’s zoom in a bit… Uh oh, we’re not quite there. 1.415? Close, but zooming in a bit more we can see we still overshot it. How long is this lousy diagonal line?! It’s length doesn’t seem to be representable in ordinary integers or fractions…

Have we made some mistake? This extremely regular shape has already produced for us a bit of a quandary; we’re just trying to measure the length between a square’s two corners! It’s as if Well, whatever the length is, let make a square out of it too. Two squares might be easier to compare

Take a minute to look at the two squares. Notice anything? It looks to me like half of our original square fits inside this new square exactly 4 times. 4 halves make 2 wholes, so 2 original squares = 1 new, diagonal square.

Let’s see if we can find that diagonal now! We know that two squares whose sides are 1 add up to form a bigger square, whose side we don’t know (besides knowing it’s close to 1.4). Let’s call that side length d, for diagonal. So, we can say $12+12=d^2$.

Since 12 is just 1x1, which equals 1, and since 1+1=2, we know that $d^2=2$. This says that our diagonal squared is equal to 2. We are almost there! At this point, you might just take the square root of both sides: the square root of $d^2= d$, and the square root of 2 is, well, $\sqrt 2$. So the diagonal of a square with side lengths of 1 is equal to $\sqrt 2$.That’s not satisfying at all! …what is this $\sqrt 2$ business?

How to Find √2

We know that our diagonal line d, times itself, equals 2, or $d^2=2$, that’s just saying that $d \times d=2 \ or \ d=\frac{2}{d}$ (if we divide both sides by d). We got close earlier just by measuring; we found that the diagonal length was less than 1.5, and probably around 1.4.

Let’s let 1.5 be our first guess for d and then see if we can refine our guess to get closer to the answer: so d=1.5… since d=2/_d, _we should divide 2 by 1.5 to see what we get:

- DIVIDE 2 BY OUR GUESS:

$$2 / 1.5 = \mathbf{1.\bar{3}} \ \ \text{ ...or in fractions,} \frac{2}{\frac{3}{2}}=\mathbf{\frac{4}{3}} $$

So, we know that 1.3 x 1.5 = 2, but we want 1.3 and 1.5 to be the same number: we want d x d = 2. Our next guess should be a number in between these two numbers, so lets average them!

-

GET A NEW GUESS (average the old guess and the quotient):

$$\frac{(1.5 + 1.3)}{2} = \mathbf{1.41\bar{6}} \ \ \text{ ...or in fractions,} \frac{(3/2) + (4/3)}{2} = \mathbf{\frac{17}{12}} $$ -

REPEAT

Our next guess is $1.41\bar{6}$, so we can do this process over again: divide 2 by our guess, and take the average of the quotient and the divisor:

$$\frac{2}{1.41\bar{6}} = \mathbf{1.4\overline{117647058823529}} \ \ \text{ ...or in fractions,} \frac{2}{(17/12)}= \mathbf{\frac{24}{17}} $$

We know the answer is somewhere in between $1.41\bar{6}$ and $1.4\overline{117647058823529}$, that is, between 17/12 and 24/17. Average them!

$$\frac{(17/12)+(24/17)}{2} = 1.414215... \ \ \text{ ...or in fractions,} \mathbf{\frac{577}{408}} $$

If we were to repeat this process forever, we would converge on the square root of 2, which is the length of that diagonal. But until we do an infinite number of these averages, we won’t know exactly how long the diagonal of a square is! Unbelievable! Chances are, you’ve already whipped out your calculator and found that $\sqrt{2} = 1.414213562...$, so our averaging method worked well! After just 3 iterations, we’re off by only 0.000015%! What does it mean, though, that this “irrational” hole to infinity emerges when we try to do something as basic as measure a square? What does it mean?

What About π?

I don’t know about you, but no one ever showed me what $\pi$ (pi) was all about. I mean sure, as far as numbers it is culturally unique in having, for whatever reason, made its way onto t-shirts and bumper stickers like some kind of geek heraldry. we hear over and over again that this 3.14 is some number equal to ~22/7, and know it has to do with circles because we had to memorize that $A=\pi r^2$ and $C=2\pi r$. We may even know that it’s “the ratio of the circumference to the diameter,” which is simply a restatement of the formula $\pi=\frac{2r}{C}=\frac{d}{C}$. But what is $\pi$, what does it look like, and what do these equations really mean? Paul Lockhart discusses the educational disasters that can accompany this topic:

So let’s talk about $\pi$, not because we have to memorize it, but because it is weird and fascinating and very much worth thinking about for its own sake!

Above, we talked about how, when you take a square’s diagonal and divide by its side, weird stuff happens (you get $\sqrt{2}$). Even weirder stuff happens when you measure around a circle (circumference) and divide by the distance across (diameter): you get $\pi$. Humans have been refining their calculations of this value since at least 1850 BC. People first noticed that, for any given circle, the distance around a circle is about 3 times the distance across. But as the figure above illustrates, this is not quite right: 3 diameters around almost gets us there, but leaves us coming up short by somewhat more than 14 hundredths. But how much more, exactly?

Around 250 BC, Archimedes came up with a new approach: because we can measure straight lines but not curves, just stick the circle inside a shape made from only straight lines (i.e., a polygon), and increase the number of sides to get closer and closer to a circle. Then measure the straight lines around the outside.

Here’s an example of Archimedes' influential technique: put a circle with a diameter of 1 exactly inside a square: Our first guess for the area of a circle is the number of sides of the square times the length of each one (the perimeter of the square), which in this case is 4. To home in our $\pi$, we keep increasing the number of sides and multiplying by the length of each one, as shown above for four more polygons (a hexa-, octa-, dodeca-, and 24-gon). Notice that, even when approximating with a 24-sided shape, our guess comes up pretty short (3.15966).

Using this method, Archimedes proved that 3.1408 < π < 3.1429. More than 1800 years later, humans were still using this technique: the record in 1630 for calculating digits of π was 39 (this record still stands as the most accurate manual geometric calculation of π).

If you want to calculate these yourself, you need to know the side length of your n-gon. This can be calculated using the tangent function, opposite over adjacent. Since the radius is 1 in our case, we just do $tan(\pi/n)$ where n is the number of sides.

Infinite Series Calculations of π

This kind of calculation results when a pattern of numbers, being summed or multiplied repeatedly, converges on a mathematical constant (or some fraction thereof).

Though an Indian mathematician named Nilakantha discovered the idea of using an infinite series to calculate π around 1500, they weren’t used in the West until the 1600s. Old Nilakantha’s series is actually pretty good:

After 4 terms it’s at 3.1452…! The first known Occidental series was this one, found by Fracois Viete:

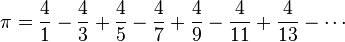

Notice that it is less than ideal because it depends on the square root of two, another difficult number. In the 1670s, the Gregory-Leibniz series was found:

The 20th century gave us computing and iterative algorithms that are calculating ever more digits. Interestingly, it also saw several new infinite series that are faster than these iterative algorithms and less memory-intensive. Ramanujan found this one in 1914:

And in 1987, the Chudnovsky brothers came up with this bad boy, which produces about 14 digits of pi per term!

Needless to say, it was used for several record-setting calculations including the first to surpass 1 billion digits (1989) the first to surpass a trillion (2009), and 10 trillion (2011).

Area of a Circle

One last thing for now: since we talked about pi, and since we talked about the area of squares (and triangles), we should definitely end with the area of a circle. For this, you probably memorized the formula A=πr2, but what does this mean? It means that if we take the radius, make a square out of it, and multiply that square by pi, we have the area. Can we connect this to the way we found the area above, i.e, length-x-width or base-x-height? Absolutely!

Imagine unpeeling tiny layers from a solid, filled-in circle and laying them side by side until there are no layers left (as in the picture below). The first layer you peel off is a circumference (its length is 2πr) the next layer is a tiny bit shorter, and the next is shorter still, and so on… Eventually, you will have unpeeled your whole circle to form a triangle with a base as long as the radius of the circle and a height as long as the circumference: this is the top triangle in the picture. Well, what’s the area of this triangle? (Base x Height)/2, right? So that’s radius times circumference divided by 2, or (2πr x r)/2 = πr2 = Area!

-

Here’s why: dividing π by the number of sides gives us the degree measure of the the top angle in a triangle formed by connecting the polygon’s to the center of the circle. Half of this measure is the angle measure of the right triangle shown above; if we take the tangent of this angle, it gives us the value of opposite/adjacent: = (s/2)/(1/2) = s. AWESOME! Since _s _is our side length, we found that simply taking tan(π/# of sides) gives us the length of one of those sides (in the case where the diameter is 1). In general, the length of the side is found by multiplying tan(π/n) by the diameter. ↩︎