Sorry to have been so long away from the blog! The purpose of this post is to give some intuition for Euler’s identity (“the most beautiful theorem in mathematics”) to those who haven’t seen it before or to those for whom it is meaningless because they lack the math background.

This was never introduced to me in any class, and unless you majored in math or physics the same is probably true for you. I wanted not only to call your attention to this equation, but also to derive it, the derivation of which is equally marvellous. Walking through it with a pencil was perhaps my first real taste of what I imagine mathematicians live and breathe for; my present aim is to give you a taste!

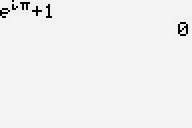

Well, here it is:

It’s pretty astounding when you look at it for the first time… it seems a ridiculous assertion! (However, Gauss is supposed to have said that if this was not immediately apparent to you on being told it, you would never be a first-class mathematician.) He also had a really cool signature, so he is probably right.

Really though? Are we talking about $e \ (2.71828...)$, like from continuously compounded interest? You mean $\pi \ (3.14159...)$, like a circle’s circumference-to-radius ratio? And the imaginary number i, the square root of -1, that we talked about for like a week in high school and then never actually used for anything? Yep, those are the ones: e, π, and i. Dust off your old TI-8x, punch this badboy in, and see what output you get. The batteries are probably dead so I’ll spare you the trouble:

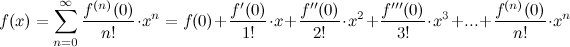

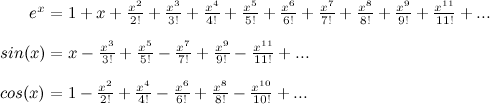

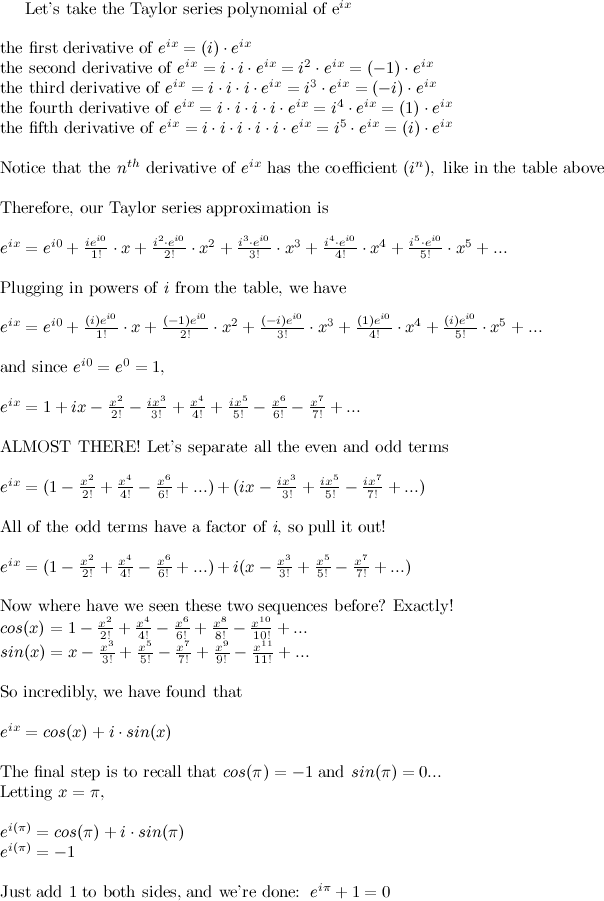

Though I am mainly interested in showing you a way to get to this shocking identity, I will need thereby to talk a bit about Taylor series approximations. If you don’t know much about this technique, think of using a sum of polynomials to approximate the shape of function at a given point. If you don’t know much about polynomials and functions, think of adding together easy-to-compute things ($x, x^2, x^3,_ ...$) to approximate hard-to-compute things ($e^x, \sin(x), \ln(x),...$). This is actually how your calculator computes with things like $e, \pi, etc.$

But this isn’t a post about Taylor series approximations, so I’ll cut down on the details. If you already understand how to use Taylor series approximations, you could skip to the derivation. If you don’t, it is super useful and cool, so check it out! First things first: if you want to approximate the shape of a function $f(x)$ using an easier-to-work-with polynomial like a power series (i.e., $a + bx + cx^2 + dx^3 ...$ where $a, b, c, d$,… are constants), you can do it like this:

where $f^{(n)}(0)$ represents the nth derivative of function $f(x)$, evaluated at x=0 (this gives us the shape around x=0).

$f(x)$ using polynomials instead. Don’t worry, I’m not going to ask you to do any calculus (though you might want a helpful refresher on derivativesTo follow the derivation, you just need the following 3 results: the derivative of $sin(x)$ is $cos(x)$, the derivative of $cos(x)$ is $-sin(x)$, and the derivative of $e^x$ is itself, just $e^x$.

Let’s do $sin(x)$ first, because I’ve got some pretty pictures of it!

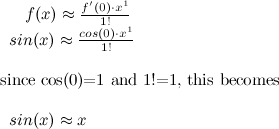

We want to approximate this function using a Taylor series polynomial. Let us do so by taking the first term of that big summation formula above. Approximating with only the first term, we have

So using only 1 term, our approximation is the line y=x

Not a very satisfying approximation, is it? What about 2 terms?

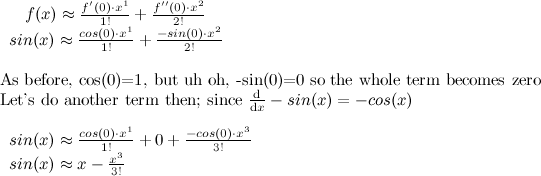

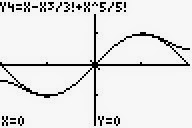

If we plot $x - \frac{x^3}{3!}$, we get

Hey wow, that’s a lot better! The polynomial $x - \frac{x^3}{3!}$ seems to pretty exactly mimic the curve for $sin(x)$, at least around x=0. Let’s add another term.

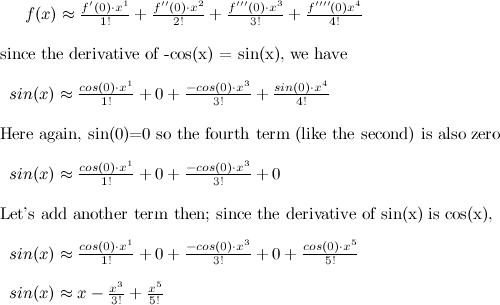

Now our approximation is $y = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!}$ which looks like this:

Even better! You can see that by adding more terms of the Taylor polynomial, we get a closer approximation of the original function. Here’s a couple more terms just to illustrate:

And plotting both,

Now the polynomial approximation is virtually indistinguishable from $sin(x)$, at least at from $x=-\pi \ to \ x=\pi$. Here’s a more “moving” display of this (credit). Notice how adding more and more terms gets us an ever-better approximation of $sin(x)$.

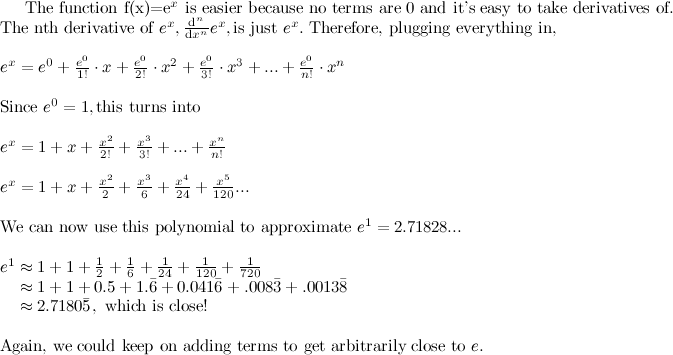

Here’s an even easier example! (We are going to need this result too.)

So we have Taylor series approximations for $sin(x)$ and for $e^x$. Now all we need is one for $cos(x)$ and we will have all of the ingredients we need! It is just like $sin(x)$ except all of the opposite terms cancel out! I’ll leave this as an exercise to the reader and just give you the result:

Take a minute to look these over. Strange, isn’t it? If it weren’t for those negative signs, it looks like simply adding $sin(x)$ and $cos(x)$ would give us $e^x$… Hmmm.

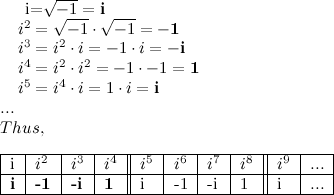

We are now in a position to make some magic happen, but one more thing remains to be done. Now’s the time to recall your imaginary number i, which is equal to $\sqrt{-1}$. Since $i=\sqrt{-1}$, we know $i^2 = -1$. For higher powers of i, we have the following pattern:

The pattern $i, -1, -i, 1,...$ repeats itself as you take ever higher powers of i. Notice that the signs are switching too! You should be excited about this. Now we’re ready for the main event!

YEAH! WOOHOO! At least, that’s how I felt when I first saw it.

YEAH! WOOHOO! At least, that’s how I felt when I first saw it.

And it’s not just superficially beautiful either. Before we plugged in $\pi$, we saw that $e^{ix}=\cos(x) + i\times \sin(x)$. This formula has many important applications, including being crucial to Fourier analysis. For an excellent introduction, check this out.

Well, I hope that if the derivation didn’t leave you reeling in perfect wonderment, you were at least given something to think about! Thanks for reading!

-

Technically, this is a Maclaurin series. ↩︎

-

Quick derivatives refresher It may be helpful to think of the derivative of a function f(x)—symbolized as d/dx f(x) or f'(x)—as a machine that gives of the slopes of tangent lines anywhere along the original function: if you plug x=3 into f'(x), what you get out is the slope of a line tangent to the original function f(x) at x=3. Since slope is just rise-over-run, the rate at which a function is increasing or decreasing, the derivative gives as the rate at which the original function is increasing or decreasing at a single point. If f(x) is the parabola x2, then its derivative f'(x) is 2x. At x=0, the very bottom of the parabola, we get f'(0)=2(0)=0, which tells us the line tangent to x2 at the point x=0 has zero slope (it’s just a horizontal line). At x=1, the parabola has started to increase; the rate it is increasing at that point (the slope of the line tangent to that point) is f'(1)=2(1)=2; so now we have a line that goes up 2 for every 1 it goes over. At f'(2)=2(2)=4, a line that goes up 4 for every 1 it goes over. This agrees with our intuition when we look at a parabola; it is accelerating upward at an ever increasing rate. ↩︎